Many critics of libertarianism argue that there have never been an anarchic society or purely free markets. I am not completely sure what they are trying to say by that (most arguments they make using those two facts are fallacious non sequiturs), but here is why the whole approach is wrong. (This is ignoring the fact that there have been societies like medieval Ireland or Iceland, where law, for example, was anarchic. I.e., the government was not in charge of law production or enforcement. There were still kings, but they didn't write the laws.)

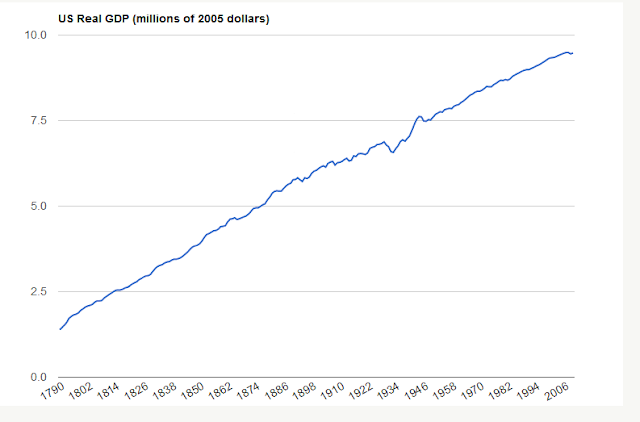

One can analyze carefully what made societies prosper and/or fail, both legally (i.e., what promoted or reduced justice) and economically (i.e., what promoted or reduced prosperity). I think such an analysis reveals that specifically freedom-promoting principles that specific societies adhered to allowed them to prosper, while adherence to anti-libertarian principles acted detrimentally and was eventually the cause of the societies' downfall and/or transformation.

There are multiple reasons for this, but the basic one is that freedom promotes competition and exploration, and those promote the best adaptation of a society to its conditions and realization of its goals. If one centralized organization is trying to find a solution, it will always do so worse than ten organization (or individuals) doing the same and competing/comparing notes with each other. This is why increased freedom leads to increased prosperity.

(Incidentally, this is true about all natural systems. Greater freedom leads to greater adaptability. When a bird learns a song, its brain creates many semi-randomized patterns of motor commands (the notes for the song, if you will) of which the bird picks the best variation; this repeats until the bird, through such neurological experimentation, finally learns the song.)

What about legal freedom? The whole concept of law is to promote peace and cooperation. It is the alternative to violence, by definition. (That is why law produced by the government is oxymoronic unless it happens to coincide with the "natural law", the natural ways to peacefully resolve conflicts.) When and where violence was embedded in a society's legal system, it led to arbitrariness of justice system, increased conflict, stifling of cooperation, and increased tyranny. Those led to decreased economic freedom and decreased prosperity. When freedom and respect for peaceful, non-violent resolution of the conflicts (which is the basis of natural law) were favored, there was increased cooperation, decreased violence and tyranny, and increased prosperity.

I won't prove this principle on one foot. There are many examples, from Roman Empire to modern Europe and US. (I don't know much about the history of East Asia, but I believe the same must be true about it too.) In every society, "pockets" of freedom within its legal and financial framework allowed it to prosper, while "pockets" of tyranny led to stagnation and eventual death.

Unfortunately, British society, where the great respect for freedom was cultivated for centuries, has turned its back on freedom in the 20th century. No wonder that it is at the same time a police state and a European hub of criminal activity. No wonder London is called "the most expensive third-world capital".

We are yet to see what direction the American society will take. That direction will determine its fate.

* * *

For analysis from legal perspective (that inspired the above thoughts), see this quote by Roderick Long analyzing Lysander Spooner's legal views:

Apparently, then, the immanent presence of natural-law maxims in the legal tradition is not confined to America but stretches back through the English Common Law to Roman law and beyond.

But just why is it the case that all these different historical legal systems have enshrined libertarian natural-law principles in their maxims? After all, it’s not as though Spooner supposes that most of these systems have been especially libertarian in practice; on the contrary, he assures us that “[a]ll the great governments of the world – those now existing, as well as those that have passed away – have been .... mere bands of robbers, who have associated for purposes of plunder, conquest, and the enslavement of their fellow men.” (Natural Law I.3.2, p. 18.)

His answer, it seems, is that some degree of reliance on libertarian principles is necessary in order to have a workable social order: the conditions on which “mankind can live in peace, or ought to live in peace,” are “first, that each man shall do, towards every other, all that justice requires him to do; as, for example, that he shall pay his debts, that he shall return borrowed or stolen property to its owner, and that he shall make reparation for any injury he may have done to the person or property of another, and “second … that each man shall abstain from doing to another, anything which justice forbids him to do” such as “theft, robbery, arson, murder, or any other crime against the person or property of another.”

So long as these conditions are fulfilled, men are at peace, and ought to remain at peace, with each other. But when either of these conditions is violated, men are at war. And they must necessarily remain at war until justice is re-established.

Through all time, so far as history informs us, wherever mankind have attempted to live in peace with each other, both the natural instincts, and the collective wisdom of the human race, have acknowledged and prescribed, as an indispensable condition, obedience to this one only universal obligation: viz., that each should live honestly towards every other. (Natural Law I. 1. 1, pp. 5-6.)

In short, libertarianism is simply the consistent application of those norms whose approximate application is a universal precondition of peaceful coexistence. Even a sadistic tyrant needs most of his subjects to be cooperating peacefully with one another most of the time if he wishes to retain any power. It is thus no wonder – and no accident – that legal systems have historically appealed, at least to some extent, to libertarian principles – which is why they are there in the legal record for Spooner to find and invoke them.

*

*