It is said that even if Hashem did not give us the land of Israel and the Holy Temple, just bringing us to Mt. Sinai would be enough. The famous question is asked: what do you mean, it would be enough? The whole point of bringing us to Har Sinai is to give us Torah, which we would keep in Eretz Yisroel. The answer is that it would be enough, because when Jews received Torah, they were unified as one person. (We learn that Jews were tired before receiving of Torah. Why were they tired? Because it took them an effort to become unified. We learn from this that Jews get their strength from argument, which is why the main pastime of a frum Jew is to learn Gemara and argue.)

Being unified “would be enough”, because unity amongst Jews results in the unity between the holy Names of G-d, between Him and His Presence, and between Him and this world. (For a detailed kabbalistic explanation of this process, see Derech Mitzvosecha, mitzvas Ahavas Yisroel. Suffice it to say that each Jewish soul contains sparks from all the other Jewish souls, and unification “below” draws forth the unification “above”.)

This is why it is said that loving your fellow as yourself is the basis of the whole Torah. The point is not so much that the purpose of Torah is to bring peace amongst people (how exactly does putting on tefillin result in peace?), but that all Torah mitzvos accomplish the same thing that the single mitzva of ahavas Yisroel accomplishes: unity between G-d and His Presence in this world. And this is the whole purpose of creation and giving of Torah.

Now, the concept of unity is a tricky one. How can two separate entities become unified? This problem of disunity existed throughout the history of creation and of Jewish people. It all started from shviras ha’keilim, the breaking of the vessels of the chaotic world of Tohu (don’t worry, I won’t talk about that in detail now). The sfiroes of Tohu did not get along, couldn’t cooperate, each thinking of itself as the most important one — and kabloom! Chernobyl b’ruchnius.

And the story repeated itself many times and indeed still goes on today. The theme of disunity is the theme of Omer. As everyone knows, the students of Rabbi Akiva quaralled, had no respect to each other, and a plague sent by G-d and augmented by socialized healthcare system killed many of them, r"l, in this very period of time.

But what does it mean that they quarreled? These were the greatest sages of their generation, and they couldn’t get along? What were their disagreements about? What were the disagreements of the Jews in the desert about that they had to put aside to receive Torah? Now that we are writing a string of questions, what was the deal with the sferoes of Tohu? We shall examine these answers after the commercial break.

The Rebbe writes in the sicho devoted to Lag B’Omer that you can’t really blame the Jews in the desert, the spheroes, the students of Rabbi Akiva. They were not arguing about petty matters. They were not practicing sinas chinum. They didn’t care about chitzoinius (“your shtreimel looks worse than my hat”). Each of them had a shitta. Each of them had a job to do, a role that they played. And they took that job seriously.

Think about it: if Chessed is merciful, and it’s taking its own job as the source of mercy seriously, how can it tolerate Gevurah? What do you mean, gevurah? Chessed! And Gevurah had the same attitude. In order to “live and let live”, to “agree to disagree”, one has to take a slightly mild view of one’s own shitta. Look at it with a bit of sense of humor. And these guys couldn’t afford doing that. They were responsible agents of their missions. The sages really believed, each of them, that they were right. Of course, each one of them was, but it’s all nice and good for us, sitting here in our b’dieved armchairs, to say “eilu v’eilu”. For these people, their shittos were their whole world.

So, what is one to do? Well, says the Rebbe, this is a serious problem. This is not just a problem for the sages or spheroes or the Jews in the desert. This is a problem for any two people that are trying to create a relationship. Any kind. Two friends, two colleagues, a husband and a wife, a parent and a child, etc. How can two people become one? What do you mean, one? If I am X, I am X. I cannot be Y. I can tolerate Y. I can respect Y. I can agree to disagree, even, but to be absolutely completely unified with Y? But then what happens with my identity, my “job” (which I take seriously) of X?

Elsewhere (Inyanei Toras HaChassidus), the Rebbe explains that giluim (revelations) of G-dliness are always in conflict with each other. Because, as explained above, in order for each gilui to be itself, it must be itself and nothing else. Gevurah is Gevurah. End of story. That is why we can’t eat meat with milk. Meat is Gevurah; milk is Chessed. They don’t mix well.

But the Essence of G-d, says the Rebbe, does not have that problem. Because the Essence includes all the revelations in itself (in potential). So, when the Essence is brought into play, no threat to the identities of individual revelations happens — and they can co-exist. Which is why G-d Himself can disobey rules of logic and do things that are mutually exclusive. Which is why, when Moshiach comes and G-d’s Essence is revealed (may it happen now), there will be no contradiction between the fact that G-d is revealed (which, under normal circumstances, would destroy this world) and, at the same time, the world exists and is a world, with its physical matter. (And, incidentally, we shall be allowed to eat meat and milk together.)

So, what’s the solution to disunity? Bring G-d into the equation. When the spheroes gain the awareness that each of them is not just Chessed or Gevurah, but Chessed and Gevurah that are each doing a job for G-d, this awareness allows them to co-operate, since each of them is doing essentially the same thing (serving G-d), albeit in a different way. The deepest identity of Chessed is not its vessel, but its Light, and the whole point of the Light is the idea that it’s on a mission from G-d (“light reveals the luminary”). Furthermore, this co-operation allows them to do their jobs better. And voilá, the world of Atzilus (aka Tikkun) is here. Jews are given Torah. Sages stop dying.

And two people become one. This is the only way. In order for a relationship to be that of true, absolute unity, not just tolerance, one needs to bring G-d into it. G-d in the relationship is what allows the two people to become completely one and at the same time each retain his-or-her unique identity.

Gutt Yom Tov, y’all. May we merit to see speedily the time when the greatest unity of all possible is achieved: that between G-d and His nation, with the coming of Moshiach.

Showing posts with label marriage. Show all posts

Showing posts with label marriage. Show all posts

Friday, May 11, 2012

Tuesday, November 29, 2011

Leaving options open

When you surround an army, leave an outlet free. This does not mean that the enemy is allowed to escape. The object is to make him believe that there is a road to safety and thus prevent his fighting with the courage of despair.

— Sun Tzu, The Art of War, Ch. VII

When talking about relationships, Rabbi Gottlieb compares the above to the difference between being married and dating. When one is married, one is "sealed in" (although one can still get divorced, chv"sh, the barrier to do so is much higher than to breaking up). As a result, any problem that one encounters, one will fight on much more severely and stubbornly than if one were merely dating. Even if one is in a so-called "long-term relationship" — let's say, a couple has been together for close to a year — it is much easier to break up over the same problem that one might encounter during one's shanah rishoina.

I think the same distinction applies not only to secular-style dating, but even to the shidduchim. On the one hand, one wants to find out as much as possible about his perspective spouse. On the other hand, certain things are better left unknown — until the couple are married, when such things should be dealt with. Once one is "sealed in", one fights with a greater effort and can accomplish things he did not know he could.

I am talking about things that can theoretically be solved within the context of marriage (i.e., there is a good chance that the couple can deal with them — even with some difficulty — once they come up). Obviously, many things should be known before one commits. It is a matter of balance. I suspect that the balance may be off-set in the modern shidduchim, contributing to so many people unable to find a partner for a long time.

This also touches on the idea of length of a shidduch. The shorter the shidduch, the less one finds out about one's perspective spouse. This has the danger of remaining ignorant of things that one better find out about before one is married. But the longer one dates, the more one is likely to find something out that will ruin the general "mood" of the shidduch — something that could be certainly dealt with once the couple were married.

That is why in certain communities (including, to a large extent, Lubavitch community), the general custom is to find out about the most important, crucial things, and leave the rest to be worked on during the first year of marriage.

* * *

In a game of go, one is oftentimes confronted with choices. It goes without saying that there are many choices of good moves on the board during most of the game. But sometimes one has a choice between specific moves in a specific location. For instance, if I play 1a, my opponent will respond 2a, to which I will respond 3a. If I play 1b, he will respond 2b, and I will respond 3b. Etc. The micro-situation on the board will change depending on my move.

The idea I heard a few days ago is that sometimes it is useful not to play any of the choices and just tenuki — play somewhere else on the board. (The important assumption is that the sequences a, b, and c have equal value to me. Obviously, if 1a–2a–3a exchange is more valuable than the others, I should play 1a.)

Why tenuki? Well, the point is that the situation on the board is still uncertain. Let's say, the center and the right side of the board are still unsettled. Although I may have some semblance of a plan of what I want to do, I don't know perfectly how my opponent will respond. Because of this, a situation may arise on the board that favors 3b move over 3a or 3c. But if, at that point, I will have already played 1a, it will be too late to take advantage of 3b. So, best leave things unsettled, sequences still hanging in potential, until the situation changes and I have a better idea of what is more beneficial to me.

What if the opponent chooses one of the sequences himself? Well, in that case, you will respond accordingly — and you will have played (hopefully sente) somewhere else on the board first.

Last night, a situation like that actually happened. I was playing a game in a local Barnes and Noble coffee shop and had a group on the left in which there was a choice of how to make two "eyes" (two independent sets of internal liberties necessary for the group to live). The game moved on, and the bottom and the center of the board got settled. The group which was pushing on the my left-side group from the outside found itself in a shortage of liberties if I played the right tesuji (a combination of moves). But, this tesuji was possible only because I left the left-side group alone, having not chosen in which of the two ways I can make eyes. (Obviously, if my opponent would make a move there, I would have to respond. But, he also left the group alone.)

* * *

The above concept from go can be applied to everyday life in a number of ways. The obvious lesson is to leave the options open. Don't burn the bridges. Don't seal things in until you have to. In relationships too, sometimes it is helpful not to make up one's mind about a person and leave a space for the development of the relationship and your opinion about him.

In one of his articles (most of which I happen to dislike, but this one is good), Tzvi Freeman compares it to an advice that most of us heard at some point of our lives: don't tighten the screws all the way until all of them are in. You may want to leave some "wiggle room" for things to re-adjust.

In one of his articles (most of which I happen to dislike, but this one is good), Tzvi Freeman compares it to an advice that most of us heard at some point of our lives: don't tighten the screws all the way until all of them are in. You may want to leave some "wiggle room" for things to re-adjust.

* * *

Something interesting: miai (read until the end of the introductory section).

Tuesday, May 11, 2010

Brotherly love

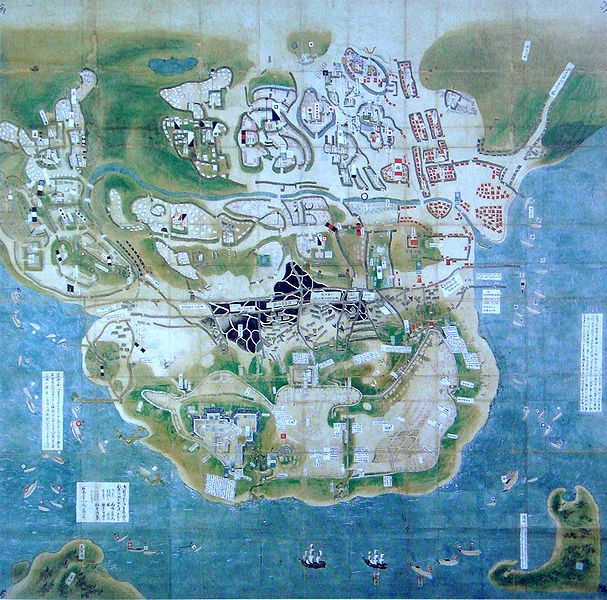

(click on the image to enlarge)

There are many “modern” ways to read into the deeper meaning of this ancient, proud Slavic song, but we shall stick to the traditional interpretation: that cossacks valued friendship and a warrior’s duty over love (and I use the last word in a very general sense).

The song is sung in a slow or quick tempo (the translation is not the best, but it will do):

From beyond the wooded island

To the river wide and free

Proudly sailed the arrow-breasted

Ships of Cossack yeomanry.

On the first is Stenka Razin

With his princess by his side

Drunken holds in marriage revels

With his beauteous younger bride.

From behind there comes a murmur

"He has left his sword to woo;

One short night — and Stenka Razin

Has become a woman, too."

Stenka Razin hears the murmur

Of his discontented band

And his lovely Persian princess

He has circled with his hand.

His dark brows are drawn together

As the waves of anger rise;

And the blood comes rushing swiftly

To his piercing jet-black eyes.

"I will give you all you ask for

Head and heart and life and hand."

And his voice rolls out like thunder

Out across the distant land:

"Volga, Volga, Mother Volga

Wide and deep beneath the sun,

You have never seen such present

From the Cossacks of the Don.

So that peace may reign forever

In this band so free and brave

Volga, Volga, Mother Volga

Make this lovely girl a grave."

Now, with one swift mighty motion

He has raised his bride on high

And has cast her where the waters

Of the Volga roll and sigh.

"Dance, you fools, and let's be merry

What is this that's in your eyes?

Let us thunder out a chantey

To the place where beauty lies."

From beyond the wooded island

To the river wide and free

Proudly sailed the arrow-breasted

Ships of Cossack yeomanry.

Now, amongst the historians there is a great degree of disagreement regarding the question of whether Stenka Razin really did drown the Persian princess (whom he held as a hostage) and if he did, what his reasons might have been. I have just perused a work analyzing this important chapter in Russian national history. It quotes different sources, going back to such authorities as Jan Jansen Streiss (1630–1694), Dutch “sailing master” working on a Russian ship, and Louis Fabricius (1648–1729), Dutch emissary to Persia. Let me tell you: the answer is not so simple.

Besides the traditional view presented in the mighty hymn above, another opinion says that she jumped herself after discovering that she was pregnant, but a careful analysis from military historians pointing at the time when the princess might have been captured debunks this view.

Some sources present a view that she was sacrificed to the cossack deity that was associated with either Caspian sea or Volga (like most Christians, the cossacks were rather liberal in their religious beliefs and were not bothered by the conflicts of mono- and polytheism; of course, when the time came to kill someone else for his religious beliefs, they became rather orthodox). You see, before the cossacks departed on a raiding expedition to Caspian sea (as all Russians know, river Volga flows into Caspian sea¹) they would bring sacrifices to both the river and the sea — oftentimes human ones. For Halachic reasons, I cannot tell you the name of their maritime deity, but what I can say is that it is also the name of one American hurricane of the past.

In any event, this wouldn’t be the first time someone sacrificed his (or her) family for religious beliefs. Although a counter-argument states that if Razin had a Persian princess as a newly-acquired captive, he would be sailing up river Volga, away from the Caspian sea and Persia, not towards them.

In reality, eastern Cossacks did capture Persian women and even settle in a colony called Persiánovka, where they started off families with their captives. Due to the mobile nature of their enterprise, however, the colony did not endure.

After the Shvuos, I will present, iyH, the different musical versions of the song.

______________

¹ “And Volga flows into Caspian sea” is a Russian way of saying “duh” — i.e., stating an obvious (and sometimes useless) fact. This map confirms this fact. Also, it shows how long the river is: it starts north of Moscow and goes all the way to Caspian sea, north of Iran. Russia in general is known for its long rivers.

By the way, these cossacks were known as Don Cossacks, because the river Don was their main base of operation. Don and Volga are two of the three mighty Russian rivers (the third one is Dnepr). There is a place where Don and Volga come close to each other. It is a site of the city called today Volgograd, although back in the day it was called Stalingrad and was the place where one third of the whole Nazi army was encircled and destroyed by the Soviet forces.

(Of course, the three mighty rivers are those just on the European side. Siberia also sports quite a collection of long and wide waterways. One of them is called Lena and was the source of the nickname of the first leader of the Soviet Union.)

I actually wonder how a Russian version of Three Men in a Boat (telling of a journey up or down Volga, for instance) would look like.

Monday, May 3, 2010

On relationships, investments and eggs

I listened to a talk recently (while driving through upstate NY and Connecticut countryside) based on a work of mussar by a famous godol. In this talk, the author (not the godol himself, but a well renowned rabbi, whose ideas and lectures I usually enjoy and respect very much) talked about the nature of relationships from the point of view of mussar.

Friday, April 23, 2010

403291461126605635584000000

Yes, I suppose that is a bit old for shidduch. On the other hand, I would say nothing is that old in reality. Not even Atik Yomin.

Interesting fact of life: hot air goes up, but ice cream, when it melts, goes down.

Also, the latest poll has finished. Unlike the last time, when most of my readers turned out to be heretics, this poll revealed that most of my readers are fanatics. Some are religious fanatics, and some are secular fanatics (fortunately, fewer than the religious ones).

To a question: “Can a tzaddik be wrong?”, 55% answered: “He cannot be wrong about anything”, 23% answered: “He can be wrong about anything”. Only a mere minority gave the more moderate answers: “He cannot be wrong, but he can be less right” (which was my official answer) — only 3 votes (13%), and “He can be wrong, but not about Torah” — only 2 votes (including my own vote from my work computer), or 9%.

I am not going to say that the prevalent fanaticism amongst the readers of this blog is good or bad; I just think it’s interesting.

Please answer the new poll.

Thursday, April 15, 2010

The art of proposing

I know a chossid (married for ten years already and with children, b"H) who, when the time came to propose to his kallah, asked her: “Would you like to go to the Ohel with me?” He thought himself incredibly smooth. His wife (as she confessed much later, with her husband sitting there) was thinking: “What a loser.”

Here is another excerpt from Three Men on a Bummel, this time regarding proposing. I must say, this method seems much smoother than the one above, although not without inherent dangers. It is also an example of how American English sounded to me (in terms of comprehensibility) when I just came to this here country:

Here is another excerpt from Three Men on a Bummel, this time regarding proposing. I must say, this method seems much smoother than the one above, although not without inherent dangers. It is also an example of how American English sounded to me (in terms of comprehensibility) when I just came to this here country:

A story is told of a Scotchman who, loving a lassie, desired her for his wife. But he possessed the prudence of his race. He had noticed in his circle many an otherwise promising union result in disappointment and dismay, purely in consequence of the false estimate formed by bride or bridegroom concerning the imagined perfectability of the other. He determined that in his own case no collapsed ideal should be possible. Therefore, it was that his proposal took the following form:

“I’m but a puir lad, Jennie; I hae nae siller to offer ye, and nae land.”

“Ah, but ye hae yoursel’, Davie!”

“An’ I’m wishfu’ it wa’ onything else, lassie. I’m nae but a puir ill-seasoned loon, Jennie.”

“Na, na; there’s mony a lad mair ill-looking than yoursel’, Davie.”

“I hae na seen him, lass, and I’m just a-thinkin’ I shouldna’ care to.”

“Better a plain man, Davie, that ye can depend a’ than ane that would be a speirin’ at the lassies, a-bringin’ trouble into the hame wi’ his flouting ways.”

“Dinna ye reckon on that, Jennie; it’s nae the bonniest Bubbly Jock that mak’s the most feathers to fly in the kailyard. I was ever a lad to run after the petticoats, as is weel kent; an’ it’s a weary handfu’ I’ll be to ye, I’m thinkin’.”

“Ah, but ye hae a kind heart, Davie! an’ ye love me weel. I’m sure on’t.”

“I like ye weel enoo’, Jennie, though I canna say how long the feeling may bide wi’ me; an’ I’m kind enoo’ when I hae my ain way, an’ naethin’ happens to put me oot. But I hae the deevil’s ain temper, as my mither call tell ye, an’ like my puir fayther, I’m a-thinkin’, I’ll grow nae better as I grow mair auld.”

“Ay, but ye’re sair hard upon yersel’, Davie. Ye’re an honest lad. I ken ye better than ye ken yersel’, an’ ye’ll mak a guid hame for me.”

“Maybe, Jennie! But I hae my doots. It’s a sair thing for wife an’ bairns when the guid man canna keep awa’ frae the glass; an’ when the scent of the whusky comes to me it’s just as though I hae’d the throat o’ a Loch Tay salmon; it just gaes doon an’ doon, an’ there’s nae filling o’ me.”

“Ay, but ye’re a guid man when ye’re sober, Davie.”

“Maybe I’ll be that, Jennie, if I’m nae disturbed.”

“An’ ye’ll bide wi’ me, Davie, an’ work for me?”

“I see nae reason why I shouldna bide wi’ yet Jennie; but dinna ye clack aboot work to me, for I just canna bear the thoct o’t.”

“Anyhow, ye’ll do your best, Davie? As the minister says, nae man can do mair than that.”

“An’ it’s a puir best that mine’ll be, Jennie, and I’m nae sae sure ye’ll hae ower muckle even o’ that. We’re a’ weak, sinfu’ creatures, Jennie, an’ ye’d hae some deefficulty to find a man weaker or mair sinfu’ than mysel’.”

“Weel, weel, ye hae a truthfu’ tongue, Davie. Mony a lad will mak fine promises to a puir lassie, only to break ’em an’ her heart wi’ ’em. Ye speak me fair, Davie, and I’m thinkin’ I’ll just tak ye, an’ see what comes o’t.”

Concerning what did come of it, the story is silent, but one feels that under no circumstances had the lady any right to complain of her bargain. Whether she ever did or did not—for women do not invariably order their tongues according to logic, nor men either for the matter of that—Davie, himself, must have had the satisfaction of reflecting that all reproaches were undeserved.

In tandem

Recently, I have quoted to you a story about a young couple so engrossed in a conversation that they lost track of their surroundings. Here is a similar story, but with different details.

I just want to remark on the effect that marriage has on one. Before marriage, it is likely to be so focused on one’s date as to lose sense of one’s boat. After the marriage, it becomes more likely to become focused on one’s bicycle and ignore the loss of one’s wife.

Other remarks, such as one regarding men and female dresses, are also true.

Actually, last summer, when I was in Catskill Mountains, I saw a young Breslover couple (a man and a woman) on a tandem bike. They seemed to be enjoying themselves quite a bit. As I continued going downhill (this was in the Lake Minewaska area), I saw another, slightly less enthusiastic couple: a large yeshivish-looking fellow, in a suit, going up the hill, accompanied by another yeshivish man of much thinner complexion. The men were eying people coming down the hill suspiciously, but seeing a kindred spirit in me (I was wearing my beard that day), asked me how far to the top.

And now the story:

Friday, March 19, 2010

Get a job!

Jensen and Smith (Journal of Population Economics, 1990) report:

The only question is: would the above study consider husbands who warm the bench sitting and learning Gemara (and take the numerous coffee breaks) all day long employed or unemployed?

(For the cynics in the audience: no, I didn’t change my opinion of the so-called social “sciences”. I only quote from their studies when they support my point of view.)

This paper analyzes the effects of unemployment on the probability of marital dissolution. Based on panel data for a sample of Danish married couples, we estimate a dynamic model for the probability of marital dissolution where we take into account the possible effects of unemployment for both spouses. We also control for other factors such as education, age, presence of children, place of residence, health and economic factors. The empirical results show that unemployment seems to be an important factor behind marital instability. However, only unemployment of the husband has an effect, and this effect is immediate.Who knew, eh?

The only question is: would the above study consider husbands who warm the bench sitting and learning Gemara (and take the numerous coffee breaks) all day long employed or unemployed?

(For the cynics in the audience: no, I didn’t change my opinion of the so-called social “sciences”. I only quote from their studies when they support my point of view.)

Monday, December 14, 2009

Making everything the best it can be

I had a conversation with a friend yesterday, in which I confessed that I have no idea what the avoida of women in Yiddishkeit and in Chassidus is. Which is still true.

My friend answered: to make things and people the best they can be. Or something along those lines.

I could say that I have these problems and those problems with the answer, and a different set of problems with the alternative answer, but the most intelligent thing I will say is that I still don't really know. (In general, ignorance seems to be my predominant state lately.)

But seeing this joke just now (on this blog) reminded me of my friend’s assertion:

The governor of Texas and his wife are driving through a small town and getting gas. The governor notices that his wife is looking very closely at the gas station attendant filling them up. He remembers that she was born and grew up in this very town and figures out what two plus two is. After they drive off, the following conversation ensues:

— Hey, aren’t you from this town?

— Yes, dear.

— And you dated a few guys in this town before you moved to Dallas and met me, didn’t you?

— Yep, sure did.

— Hmm. This is really just a wild guess, but is there a chance the guy filling us up was one of them?

— Yeah, you got it. He was my former boyfriend. Didn’t recognize me though.

— In that case, can I ask you what you were thinking about when you were looking at him? Were you thinking that had you married him instead of me, instead of being a wife of the governor of Texas, you’d be married to a gas station attendant?

— No, I was thinking that had I married him, he would be the governor of Texas.

My friend answered: to make things and people the best they can be. Or something along those lines.

I could say that I have these problems and those problems with the answer, and a different set of problems with the alternative answer, but the most intelligent thing I will say is that I still don't really know. (In general, ignorance seems to be my predominant state lately.)

But seeing this joke just now (on this blog) reminded me of my friend’s assertion:

The governor of Texas and his wife are driving through a small town and getting gas. The governor notices that his wife is looking very closely at the gas station attendant filling them up. He remembers that she was born and grew up in this very town and figures out what two plus two is. After they drive off, the following conversation ensues:

— Hey, aren’t you from this town?

— Yes, dear.

— And you dated a few guys in this town before you moved to Dallas and met me, didn’t you?

— Yep, sure did.

— Hmm. This is really just a wild guess, but is there a chance the guy filling us up was one of them?

— Yeah, you got it. He was my former boyfriend. Didn’t recognize me though.

— In that case, can I ask you what you were thinking about when you were looking at him? Were you thinking that had you married him instead of me, instead of being a wife of the governor of Texas, you’d be married to a gas station attendant?

— No, I was thinking that had I married him, he would be the governor of Texas.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)