First, your return to shore was not part of our negotiations nor our agreement so I must do nothing. And second, you must be a pirate for the pirate's code to apply, and you're not. And third, the code is more what you'd call "guidelines" than actual rules. Welcome aboard the Black Pearl, Miss Turner.

— Captain Barbossa, Pirates of the Caribbean

A repost from elsewhere. I am answering the question: "Should we give a brother and a sister a right to get married?"

My response:

The concept of law can be summarized as "a set of rules that will allow people to live in peace and resolve their conflicts non-violently if they choose so". The alternative to law is Hobbsean jungle, where every person defends himself with violence against everyone else, basically treating all other humans as forces of nature which one can either give in to or fight. The concept of society and civilization presupposes a desire to avoid such conflicts and live in peace.

This shows that any kind of violence cannot be a part of law. Note that I am not talking about

law enforcement: that may or may not require violence (law can also be enforced through non-violent threats of ostracism, for example). I am talking about

law: figuring out, theoretically, whom a certain resource should justly belong to in a case of a conflict.

Law must be such that all members of society should agree to it. This is what separates law from morality: the latter is a rule for someone to keep even in private. If I consider stealing immoral, I shouldn't do it whether or not I will be caught. Law, on the other hand, is a public "sign" for all to read, agree to, and enforce. (In particular, because everyone agrees to a certain law, everyone finds its enforcement appropriate.) If stealing is unlawful, then we all agree to catch thieves and make them return the stolen property back to the owners (plus the costs of catching them).

This understanding of law shows that:

a) it cannot use violence or threats of violence

b) it must be a common denominator between different groups of people living in a society and even sometimes having different moral preferences.

Both principles explain why polygamy or incest or homosexual marriage cannot be considered illegal (unlawful) if we stick to the above definition of law. Laws against such activities would not be not solving conflicts; in fact, they'd be creating them!

Note that I may consider a certain behavior (for instance, eating pork or gossip) immoral, but not unlawful.

The concept of rights as interpreted through this definition (what the law should recognize as someone's right) means that the rights are not given, but

discovered (as the most rational means to promote peace in a society).

Note that Jefferson agreed to this idea in the Declaration of Independence. He starts off by saying that all people have rights deriving from their nature as rational beings (which was granted to them by the Creator, evolution, aliens, or whatever you believe in). Only then he says that in order to protect those rights, the governments are formed.

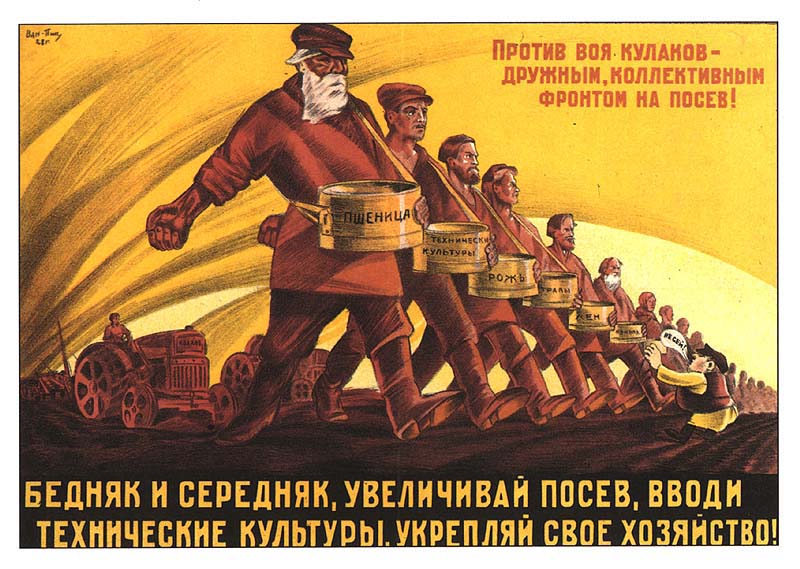

On the other hand, the same concept of law also explains why law cannot be positive: created by the government. Simply because Obama says X doesn't explain why X should be the law. X must be justified as the best way to resolve a conflict between two parties and create justice. And if X has nothing to do with conflict resolution, then it's not a law at all!

Nowadays, what is Obama's (or any other politician's) justification for declaring X a law?

a) if you disobey X, I will put you in a cage

b) 51% of the people elected me

But neither is a good justification for why X leads to greatest justice. In fact, both are threats of violence: the former, violence of the government on the people; the latter, violence of the majority on the minority.

The view that law cannot be positively declared but must be objectively discovered may sound shocking, but in fact it was the traditional view in all societies until the Enlightenment and the so-called "nation-states". Kings back in the day were not in charge of creating laws; they were in charge of adjudication, enforcement, and, more often, protection of their "subjects". If you told people that we should ask a king what the law should be, they would look confused and ask back: "Should you also ask him what 2+2 equals to?"

Here are some quotes to prove that historically, people held the above view of the law (taken from Roderick Long's essay

The Nature of Law):

"I find that it has been the opinion of the wisest men that law is not a product of human thought, nor is it any enactment of peoples, but something eternal ....

From this point of view it can be readily understood that those who formulated wicked and unrighteous statutes for nations, thereby violating their trust and compact, put into effect anything but laws. It may thus be clear that in the very definition of the term law there inheres the idea and principle of choosing what is right and true. ...

What of the many deadly and pestilential statutes which nations put in force? These no more deserve to be called laws than the rules a band of robbers might pass in their assembly. For if ignorant and unskillful men have prescribed deadly poisons instead of healing drugs, these cannot possibly be called physicians' prescriptions."

— Cicero, Laws (1st c. B.C.)

"Jurisprudence is acquaintance with things human and divine, the knowledge of what is right and what is wrong. ... These are the precepts of the law: to live rightly, not to wrong another, and to render to each his own."

— Institutes of Justinian (6th c. A.D.)

"The Roman jurist was a sort of scientist: the objects of his research were the solutions to cases that citizens submitted to him for study, just as industrialists might today submit to a physicist or to an engineer a technical problem concerning their plants or their production. Hence, private Roman law was something to be described or to be discovered, not something to be enacted – a world of things that there were, forming part of the common heritage of all Roman citizens. Nobody enacted that law; nobody could change it by any exercise of his personal will."

— Bruno Leoni, Freedom and the Law

"The Anglo-Saxon courts, called moots, were public assemblies of common men and neighbors. The moots did not expend their efforts on creating or codifying the law; they left that to custom and to the essentially declaratory law codes of kings. ... As in other customary legal systems, the moots typically demanded that criminals pay restitution or composition to their victims .... The law codes of early medieval Europe consisted largely of lists of offenses and the corresponding schedules of payments. In issuing these, Kings were not legislating in the modern sense: they were rather codifying and declaring already existing custom and practice."

— Tom Bell, "Polycentric Law," Humane Studies Review 7, No. 1, 1991/92

"Law in the sense of enforced rules of conduct is undoubtedly coeval with society; only the observance of common rules makes the peaceful existence of individuals in society possible. ... Such rules might in a sense not be known and still have to be discovered, because from 'knowing how' to act, or from being able to recognize that the acts of another did or did not conform to accepted practices, it is still a long way to being able to state such rules in words.

But while it might be generally recognized that the discovery and statement of what the accepted rules were (or the articulation of rules that would be approved when acted upon) was a task requiring special wisdom, nobody yet conceived of law as something which men could make at will. It is no accident that we still use the same word 'law' for the invariable rules which govern nature and for the rules which govern men's conduct. They were both conceived at first as something existing independently of human will. ... they were regarded as eternal truths that man could try to discover but which he could not alter.

To modern man, on the other hand, the belief that all law governing human action is the product of legislation appears so obvious that the contention that law is older than law-making has almost the character of a paradox. Yet there can be no doubt that law existed for ages before it occurred to man that he could make or alter it. ... A 'legislator' might endeavor to purge the law of supposed corruptions, or to restore it to its pristine purity, but it was not thought that he could make new law. The historians of law are agreed that in this respect all the famous early 'law-givers', from Ur-Nammu and Hammurabi to Solon, Lykurgus and the authors of the Roman Twelve Tables, did not intend to create new law but merely to state what law was and had always been."

— F. A. Hayek, Law, Legislation and Liberty

"Since it is by law that what is legislated is legislated, in virtue of law's being what is this legislated? Is it in virtue of its being some awareness, or some showing, as what is learned is learned through the science that shows it? ... Aren't right, and law, most fine? ... And wrong, and lawlessness, most shameful? ... And the former preserves states and all other things, while the latter destroys and overturns? ... So one ought to think of law as something fine, and seek it as good? ... So it wouldn't be appropriate for the wicked official judgment to be law. ... And yet even to me law seems to be some sort of judgment; but since it's not the wicked judgment, isn't it clear that law, if indeed it is judgment, is the worthy? ... And what is worthy judgment? Is it not true judgment? ... Isn't the true, the discovery of what is so? ... Law, then, wishes to be the discovery of what is so .... but men, who (so it seems to us) do not at all times use the same laws are not at all times capable of discovering what the law wishes: what is so. ... What's right is right and what's wrong is wrong. And isn't this believed by everyone ... even among the Persians, and always? ... What is fine, no doubt, is everywhere legislated as fine, and what is shameful as shameful; but not the shameful as fine or the fine as shameful. ... And in general, what is so, rather than what is not so, is legislated as being so, both by us and by everyone else. ... So he who errs about what is so, errs about the legal. ... So in the writings about right and wrong, and in general about ordering a state and about how a state ought to be organized, what is correct is royal law, while what is not correct, what seems to be law to those who lack knowledge, is not, for it is lawless."

— Plato, Minos (5th c. B.C.)

"But what is violence and lawlessness, Pericles? Isn't it when the stronger party compels the weaker to do what he wants by using force instead of persuasion? ... Then anything a despot enacts and compels the citizens to do instead of persuading them is an example of lawlessness? ... And if the minority enacts something not by persuading the majority but by dominating it, should we call this violence or not? It seems to me that if one party, instead of persuading another, compels him to do something, whether by enactment or not, this is always violence rather than law. Then if the people as a whole uses not persuasion but its superior power to enact measures against the propertied classes, will that be violence rather than law?"

— Xenophon, Recollections of Socrates (5th c. B.C.)

"When a case arises for which no valid law can be adduced, then the lawful men or doomsmen will make new law in the belief that what they are making is good old law, not indeed expressly handed-down, but tacitly existent. They do not, therefore, create the law: they 'discover' it."

— Fritz Kern, Kingship and Law in the Middle Ages

"As Augustine says, that which is not right seems to be no law at all; wherefore the force of a law depends on the extent to which it is right. ... Consequently, every human law has the nature of law only to the extent that it is derived from the law of nature. But if, in any point, it deviates from the law of nature, it is no longer a law but a perversion of law. ... when an authority imposes on his subjects burdensome 'laws' conducive not to the common good but rather to his own cupidity and vainglory .... the like are acts of violence rather than laws .... wherefore such 'laws' do not bind in conscience .... A tyrannical government is not right ... Consequently, there is no sedition in disturbing a government of this kind .... Indeed, it is the tyrant, rather, that is guilty of sedition .... If a thing is of itself contrary to natural right, the human will cannot make it right ...."

— Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiæ (13th c.)

"A human legislator does not have a perfect will, as God has; and therefore ... such a legislator may sometimes prescribe unjust things, a fact which is manifestly true; but he has not the power to bind through unjust laws, and consequently, even though he may indeed prescribe that which is unjust, such a precept is not law, inasmuch as it lacks the force or validity to impose a binding obligation."

— Francisco Suarez, On Laws, and on God as Legislator (17th c.)

"Nihil quod est contra rationem est licitum: nothing which is against reason is lawful. It is a sure maxim in law, for reason is the life of law."

— Richard Overton, A Defiance Against All Arbitrary Usurpations or Encroachments (17th c.)

"These are the eternal, immutable laws of good and evil, to which the creator himself in all his dispensations conforms; and which he has enabled human reason to discover, so far as they are necessary for the conduct of human actions. Such among others are these principles: that we should live honestly, should hurt nobody, and should render every one its due; to which three general principles Justinian has reduced the whole doctrine of law. ... [God] has graciously reduced the rule of obedience to this one paternal precept, 'that man should pursue his own happiness.' This is the foundation of what we call ethics, or natural law. ... This law of nature, being co-eval with mankind and dictated by God himself, is of course superior in obligation to any other. It is binding all over the globe, in all countries, and at all times: no human laws are of any validity, if contrary to this; and such of them as are valid derive all their force, and all their authority, mediately or immediately, from this original. ...

Those rights then which God and nature have established, and are therefore called natural rights, such as are life and liberty, need not the aid of human laws to be more effectually invested in every man than they are; neither do they receive any additional strength when declared by the municipal laws to be inviolable. On the contrary, no human legislature has power to abridge or destroy them .... For that legislature in all these cases acts only, as was before observed, in subordination to the great lawgiver, transcribing and publishing his precepts. ... [A judge is] sworn to determine, not according to his own private judgment, but according to the known laws and customs of the land; not delegated to pronounce a new law, but to maintain and expound the old one. Yet .... if it be found that the former decision is manifestly absurd or unjust, it is declared, not that such a sentence was bad law, but that it was not law; that is, that it is not the established custom of the realm ...."

— William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England (18th c.)

"But let the origin of government be placed where it may, the end of it is manifestly the good of the whole. Salus populi suprema lex esto [let the welfare of the people be the supreme law], is of the law of nature .... To say the parliament is absolute and arbitrary, is a contradiction. The parliament cannot make 2 and 2, 5: Omnipotency cannot do it. The supreme power in a state, is jus dicere [to state the right] only: — jus dare [to give the right] strictly speaking, belongs alone to God. Parliaments are in all cases to declare what is for the good of the whole; but it is not the declaration of parliament that makes it so: There must be in every instance, a higher authority, viz. GOD. Should an act of parliament be against any of his natural laws, which are immutably true, their declaration would be contrary to eternal truth, equity and justice, and consequently void: and so it would be adjudged by the parliament itself, when convinced of their mistake. Upon this great principle, parliaments repeal such acts, as soon as they find they have been mistaken, in having declared them to be for the public good, when in fact they were not so."

— James Otis, The Rights of the British Colonies Asserted and Proved (18th c.)

"... justice is an immutable, natural principle; and not anything that can be made, unmade, or altered by human power. ... It does not derive its authority from the commands, will, pleasure, or discretion of any possible combination of men, whether calling themselves a government, or by any other name.

It is also, at all times, and in all places, the supreme law. And being everywhere and always the supreme law, it is necessarily everywhere and always the only law. Lawmakers, as they call themselves, can add nothing to it, nor take anything from it. Therefore all their laws, as they call them, –– that is, all the laws of their own making, –– have no color of authority or obligation. It is a falsehood to call them laws; for there is nothing in them that either creates men's duties or rights, or enlightens them as to their duties or rights. There is consequently nothing binding or obligatory about them. ... It is intrinsically just as false, absurd, ludicrous, and ridiculous to say that lawmakers, so-called, can invent and make any laws, of their own ... as it would be to say that they can invent and make such mathematics, chemistry, physiology, or other sciences, as they see fit .... "

— Lysander Spooner, Letter to Grover Cleveland (19th c.)

"I deny that legislators make law. They create legal Acts, statutes, which may or may not coincide with real Law, and in fact seldom do. ... the great majority of such legislative Acts are intended to prevent or hamper or stop harmless and useful human action, so the enforcement of them has that lamentable effect."

— Rose Wilder Lane, The Lady and the Tycoon (20th c.)